2020-06-15

The Siege of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis - An Account and Analysis

In this anonymous submission, participants in the uprising in

Minneapolis in response to the murder of George Floyd explore how a

combination of different tactics compelled the police to abandon the

Third Precinct.

<hr>

The following analysis is motivated by a discussion that took place

in front of the Third Precinct as fires billowed from its windows on Day

Three of the George Floyd Rebellion in Minneapolis. We joined a group

of people whose fire-lit faces beamed in with joy and awe from across

the street. People of various ethnicities sat side by side talking about

the tactical value of lasers, the “share everything” ethos, interracial

unity in fighting the police, and the trap of “innocence.” There were

no disagreements; we all saw the same things that helped us win.

Thousands of people shared the experience of these battles. We hope that

they will carry the memory of how to fight. But the time of combat and

the celebration of victory is incommensurable with the habits, spaces,

and attachments of everyday life and its reproduction. It is frightening

how distant the event already feels from us. Our purpose here is to

preserve the strategy that proved victorious against the Minneapolis

Third Precinct.

Our analysis focuses on the tactics and composition of the crowd that

besieged the Third Precinct on Day Two of the uprising. The siege

lasted roughly from 4 pm well into the early hours of the morning of May

28. We believe that the tactical retreat of the police from the Third

Precinct on Day Three was won by the siege of Day Two, which exhausted

the Precinct’s personnel and supplies. We were not present for the

fighting that preceded the retreat on Day Three, as we showed up just as

the police were leaving. We were across the city in an area where youth

were fighting the cops in tit-for-tat battles while trying to loot a

strip mall—hence our focus on Day Two here.

<figcaption>

May 28: The Third Precinct during the day. It was set alight that night.

Context

The last popular revolt against the Minneapolis Police Department took place in response to the police murder of Jamar Clark on November 15, 2015. It spurred two weeks of unrest that lasted until December 2. Crowds repeatedly engaged the police in ballistic confrontations; however, the response to the shooting coalesced around an occupation of the nearby Fourth Precinct. Organizations like the NAACP and the newly formed Black Lives Matter asserted their control over the crowds that gathered; they were often at odds with young unaffiliated rebels who

preferred to fight the police directly. Much of our analysis below focuses on how young Black and Brown rebels from poor and working-class neighborhoods seized the opportunity to reverse this relationship. We argue that this was a necessary condition for the uprising.

George Floyd was murdered by the police at 38th Street and Chicago Avenue between 8:20 and 8:32 pm on Monday, May 25. Demonstrations against the killing began the next day at the site of his murder, where a

vigil took place. Some attendees began a march to the Third Precinct at Lake Street and 26th, where rebels attacked police vehicles in the parking lot.

These two locations became consistent gathering points. Many community groups, organizations, liberals, progressives, and leftists assembled at the vigil site, while those who wanted to fight generally gathered near the Precinct. This put over two miles between two very different crowds, a spatial division that was reflected in other areas of the city as well. Looters clashed with police in scattered commercial zones outside of the sphere of influence of the organizations while many of the leftist marches excluded fighting elements with the familiar

tactic of peace policing in the name of identity-based risk aversion.

May 28: Inside the liberated and gutted Target across Lake Street from the Third Precinct.

The “Subject” of The George Floyd Uprising

The subject of our analysis is not a race, a class, an organization, or even a movement, but a crowd. We focus on a crowd for three reasons. First, with the exception of the street medics, the power and success of those who fought the Third Precinct did not depend on their experience in “organizing” or in organizations. Rather, it resulted from unaffiliated individuals and groups courageously stepping into roles that complemented each other and

seizing opportunities as they arose.

While the initial gathering was occasioned by a rally hosted by a Black-led organization, all of the actions that materially defeated the Third Precinct were undertaken after the rally had ended, carried out by people who were not affiliated with it. There was practically no one there from the usual gamut of self-appointed community and religious leaders, which meant that the crowd was able to transform the situation freely. Organizations rely on

stability and predictability to execute strategies that require great quantities of time to formulate. Consequently, organization leaders can be threatened by sudden changes in the social conditions, which can make

their organizations irrelevant. Organizations—even self-proclaimed “revolutionary” organizations—have an interest in suppressing spontaneous revolt in order to recruit from those who are discontent and enraged. Whether it is an elected official, a religious leader, a “community organizer,” or a leftist representative, their message to

unruly crowds is always the same: wait.

The agency that took down the Third Precinct was a crowd and not an organization because its goals, means, and internal makeup were not regulated by centralized authority. This proved beneficial, as the crowd consequently had recourse to more practical options and was freer to create unforeseen internal relationships in order to adapt to the conflict at hand. We expand on this below in the section titled “The

Pattern of Battle and ‘Composition.’”

The agency in the streets on May 27 was located in a crowd because its constituents had few stakes in the existing order that is managed bythe police. Crucially, a gang truce had been called after the first day of unrest, neutralizing territorial barriers to participation. The crowd mostly originated from working-class and poor Black and Brown

neighborhoods. This was especially true of those who threw things at the police and vandalized and looted stores. Those who do not identify as “owners” of the world that oppresses them are more likely to fight and steal from it when the opportunity arises. The crowd had no interest in justifying itself to onlookers and it was scarcely interested in “signifying” anything to anyone outside of itself. There were no signs or speeches, only chants that served the tactical purposes of “hyping up” (“Fuck 12!”) and interrupting police violence with strategically deployed “innocence” (“Hands up! Don’t shoot!”).

May 28: A looted pawn shop east of the Third Precinct on Lake Street about to catch fire. The story spread that the previous night, the owner had shot and killed someone.

</figcaption>

Roles

We saw people playing the following roles:

Medical Support

This included street medics and medics performing triage and urgent

care at a converted community center two blocks away from the precinct.

Under different circumstances, this could be performed at any nearby

sympathetic commercial, religious, or not-for profit establishment.

Alternatively, a crowd or a medic group could occupy such a space for

the duration of a protest. Those who were organized as street medics did

not interfere with the tactical choices of the crowd. Instead, they

consistently treated anyone who needed their help.

Scanner Monitors and Telegram App Channel Operators

This is common practice in many US cities by now, but police scanner

monitors with an ear for strategically important information played a

critical role in setting up information flows from the police to the

crowd. It is almost certain that on the whole, much of the crowd was not

practicing the greatest security to access the Telegram channel. We

advise rebels to set up the Telegram app on burner phones in order to

stay informed while preventing police stingrays (false cell phone

towers) from gleaning their personal information.

Peaceful Protestors

The non-violent tactics of peaceful protesters served two familiar aims and one unusual one:

- They created a spectacle of legitimacy, which was intensified as police violence escalated.

- They created a front line that blocked police attempts to advance when they deployed outside of the Precinct.

- In addition, in an unexpected turn of affairs, the peaceful protestors shielded those who employed projectiles.

Whenever the police threatened tear gas or rubber bullets,

non-violent protesters lined up at the front with their hands up in the

air, chanting “Hands up, don’t shoot!” Sometimes they kneeled, but

typically only during relative lulls in the action. When the cops

deployed outside the Precincts, their police lines frequently found

themselves facing a line of “non-violent” protestors. This had the

effect of temporarily stabilizing the space of conflict and gave other

crowd members a stationary target. While some peaceful protestors

angrily commanded people to stop throwing things, they were few and grew

quiet as the day wore on. This was most likely because the police were

targeting people who threw things with rubber bullets early on in the

conflict, which enraged the crowd. It’s worth noting that the reverse

has often been the case—we are used to seeing more confrontational

tactics used to shield those practicing non-violence (e.g., at Standing

Rock and Charlottesville). The reversal of this relationship in

Minneapolis afforded greater autonomy to those employing confrontational

tactics.

Ballistics Squads

Ballistics squads threw water bottles, rocks, and a few Molotov

cocktails at police, and shot fireworks. Those using ballistics didn’t

always work in groups, but doing so protected them from being targeted

by non-violent protestors who wanted to dictate the tactics of the

crowd. The ballistics squads served three aims:

- They drew police violence away from the peaceful elements of the crowd during moments of escalation.

- They patiently depleted the police crowd control munitions.

- They threatened the physical safety of the police, making it more costly for them to advance.

The first day of the uprising, there were attacks on multiple parked

police SUVs at the Third Precinct. This sensibility resumed quickly on

Day Two, beginning with the throwing of water bottles at police officers

positioned on the roof of the Third Precinct and alongside the

building. After the police responded with tear gas and rubber bullets,

the ballistics squads also began to employ rocks. Elements within the

crowd dismantled bus bench embankments made of stone and smashed them up

to supply additional projectiles. Nightfall saw the use of fireworks by

a few people, which quickly generalized in Days Three and Four.

“Boogaloos” (Second Amendment accelerationists) had already briefly

employed fireworks on Day One, but from what we saw they mostly sat it

out on the sidelines thereafter. Finally, it is worth noting that the

Minneapolis police used “green tips,” rubber bullets with exploding

green ink tips to mark lawbreakers for later arrest. Once it became

clear that the police department had limited capacity to make good on

its threat and, moreover, that the crowd could win, those who had been marked had every incentive to fight like hell to defy the police.

<figcaption>

May 28: The back of the same pawn shop on fire.

Laser Pointers

In the grammar of the Hong Kong movement, those who operate laser pointers are referred to as “light mages.” As was the case in Hong Kong. Chile, and elsewhere in 2019, some people came prepared with laser

pointers to attack the optical capacity of the police. Laser pointers involve a special risk/reward ratio, as it is very easy to track people using laser pointers, even when they are operating within a dense and

active crowd at night. Laser pointer users are particularly vulnerable if they attempt to target individual police officers or (especially) police helicopters while operating in small crowds; this is still the case even if the entire neighborhood is undergoing mass looting (the daytime use of high-powered lasers with scopes remains untested, to our knowledge). The upside of laser pointers is immense: they momentarily compromise the eyesight of the police on the ground and they can disable police surveillance drones by interfering with their infrared sensors

and obstacle-detection cameras. In the latter case, a persistently lasered drone may descend to the earth where the crowd can destroy it. This occurred repeatedly on Days Two and Three. If a crowd is particularly dense and visually difficult to discern, lasers can be used to chase away police helicopters. This was successfully demonstrated onDay Three following the retreat of the police from the Third Precinct, as well as on Day Four in the vicinity of the Fifth Precinct battle.

Barricaders

Barricaders built barricades out of nearby materials, including an impressive barricade that blocked the police on 26th Avenue just north of Lake Street. In the latter case, the barricade was assembled out of a train of shopping carts and a cart-return station pulled from a nearby parking lot, dumpsters, police barricades, and plywood and fencing materials from a condominium construction site. At the Third Precinct, the barricade provided useful cover for laser pointer attacks and rock-throwers, while also serving as a natural gathering point for the

crowd to regroup. At the Fifth Precinct, when the police pressed on foot toward the crowd, dozens of individuals filled the street with a multi-rowed barricade. On the one hand, this had the advantage of preventing the police from advancing further and making arrests, while allowing the crowd to regroup out of reach of the rubber bullets.

However, it quickly became clear that the barricades were discouraging the crowd from retaking the street, and it had to be partially dismantled in order to facilitate a second press toward the police lines. It can be difficult to coordinate defense and attack within a single gesture.

Sound Systems

Car sound systems and engines provided a sonic environment that enlivened the crowd. The anthem of Days Two and Three was Lil’ Boosie’s “Fuck The Police.” Yet one innovation we had never seen before was the

use of car engines to add to the soundscape and “rev up” the crowd. This began with a pick-up truck with a modified exhaust system, which was parked behind the crowd facing away from it. When tensions ran high with

the police and it appeared that the conflict would resume, the driver would red line his engine and make it roar thunderously over the crowd. Other similarly modified cars joined in, as well as a few motorcyclists.</figcaption>

<figcaption>

May 28: The interior of Cub Foods, next to the Target that was looted. A large quantity of melted ice cream.

</figcaption>

Looters

Looting served three critical aims.

First, it liberated supplies to heal and nourish the crowd. On the

first day, rebels attempted to seize the liquor store directly across

from the Third Precinct. Their success was brief, as the cops managed to

re-secure it. Early in the standoff on Day Two, a handful of people

signaled their determination by climbing on top of the store to mock the

police from the roof. The crowd cheered at this humiliation, which

implicitly set the objective for the rest of the day: to demonstrate the

powerlessness of the police, demoralize them, and exhaust their

capacities.

An hour or so later, looting began at the liquor store and at an Aldi

a block away. While a majority of those present participated in the

looting, it was clear that some took it upon themselves to be strategic

about it. Looters at the Aldi liberated immense quantities of bottled

water, sports drinks, milk, protein bars, and other snacks and assembled

huge quantities of these items on street corners throughout the

vicinity. In addition to the liquor store and the Aldi, the Third

Precinct was conveniently situated adjacent to a Target, a Cub Foods, a

shoe store, a dollar store, an Autozone, a Wendy’s, and various other

businesses. Once the looting began, it immediately became a part of the

logistics of the crowd’s siege on the Precinct.

Second, looting boosted the crowd’s morale by creating solidarity and

joy through a shared act of collective transgression. The act of gift

giving and the spirit of generosity was made accessible to all,

providing a positive counterpoint to the head-to-head conflicts with the

police.

Third, and most importantly, looting contributed to keeping the

situation ungovernable. As looting spread throughout the city, police

forces everywhere were spread thin. Their attempts to secure key targets

only gave looters free rein over other areas in the city. Like a fist

squeezing water, the police found themselves frustrated by an opponent

that expanded exponentially.

Fires

The decision to burn looted businesses can be seen as tactically

intelligent. It contributed to depleting police resources, since the

firefighters forced to continually extinguish structure fires all over

town required heavy police escorts. This severely impacted their ability

to intervene in situations of ongoing looting, the vast majority of

which they never responded to (the malls and the Super Target store on

University Ave being exceptions). This has played out differently in

other cities, where police opted not to escort firefighters. Perhaps

this explains why demonstrators fired in the air around firefighting

vehicles during the Watts rebellion.

In the case of the Third Precinct, the burning of the Autozone had

two immediate consequences: first, it forced the police to move out into

the street and establish a perimeter around the building for

firefighters. While this diminished the clash at the site of the

precinct, it also pushed the crowd down Lake Street, which subsequently

induced widespread looting and contributed to the diffusion of the riot

across the whole neighborhood. By interrupting the magnetic force of the

Precinct, the police response to the fire indirectly contributed to

expanding the riot across the city.

<figcaption>

May 29: Police forming a perimeter around the Third Precinct a few hours before curfew.

The Pattern of the Battle and “Composition”

We call the battles of the second and third days at the Precinct a siege because the police were defeated by attrition. The pattern of the battle was characterized by steady intensification punctuated by qualitative leaps due to the violence of the police and the spread of the conflict into looting and attacks on corporate-owned buildings. The

combination of the roles listed above helped to create a situation that was unpoliceable, yet which the police were stubbornly determined to contain. The repression required for every containment effort intensified the revolt and pushed it further out into the surrounding area. By Day Three, all of the corporate infrastructure surrounding the

Third Precinct had been destroyed and the police had nothing but a “kingdom of ashes” to show for their efforts. Only their Precinct remained, a lonely target with depleted supplies. The rebels who showed up on Day Three found an enemy teetering on the brink. All it needed was a final push.

Day Two of the uprising began with a rally: attendees were on the streets, while the police were stationed on top of their building with an arsenal of crowd control weaponry. The pattern of struggle began during the rally, when the crowd tried to climb over the fences that protected the Precinct in order to vandalize it. The police fired rubber

bullets in response as rally speakers called for calm. After some time passed and more speeches were made, people tried again. When the volley of rubber bullets came, the crowd responded with rocks and water

bottles. This set off a dynamic of escalation that accelerated quickly once the rally ended. Some called for non-violence and sought to interfere with those who were throwing things, but most people didn’t bother arguing with them. They were largely ignored or else the reply was always the same: “That non-violence shit don’t work!” In fact,

neither side of this argument was exactly correct: as the course of the battle was to demonstrate, both sides needed each other to accomplish the historic feat of reducing the Third Precinct to ashes.

It’s important to note that the dynamic we saw on Day Two did not involve using non-violence and waiting for repression to escalate the situation. Instead, a number of individuals stuck their necks out very far to invite police violence and escalation. Once the crowd and the police were locked into an escalating pattern of conflict, the objectiveof the police was to expand their territorial control radiating outwardfrom the Precinct. When the police decided to advance, they began by throwing concussion grenades at the crowd as a whole and firing rubber

bullets at those throwing projectiles, setting up barricades, and firing tear gas.

May 29: The beauty supply section of a looted Walgreens on Lake Street, just east of the Third Precinct.

The intelligence of the crowd proved itself as participants quickly learned five lessons in the course of this struggle.

First, it is important to remain calm in the face of concussion grenades, as they are not physically harmful if you are more than five feet away from them. This lesson extends to a more general insight about crisis governance: don’t panic, as the police will always use panic against us. One must react quickly while staying as calm as possible.

Second, the practice of flushing tear-gassed eyes spread rapidly from street medics throughout the rest of the crowd. Employing stores of looted bottled water, many people in the crowd were able to learn and quickly execute eye-flushing. People throwing rocks one minute could be seen treating the eyes of others in the next. This basic medic knowledge helped to build the crowd’s confidence, allowing them to resist the temptation to panic and stampede, so that they could return to the space of engagement.

Third, perhaps the crowd’s most important tactical discovery was that when one is forced to retreat from tear gas, one must refill the space one has abandoned as quickly as possible. Each time the crowd at the Third Precinct returned, it came back angrier and more determined either to stop the police advance or to make them pay as dearly as possible for every step they took.

Fourth, borrowing from the language of Hong Kong, we saw the crowd practice the maxim “Be water.” Not only did the crowd quickly flow back into spaces from which they had to retreat, but when forced outward, the crowd didn’t behave the way that the cops did by fixating on territorial control. When they could, the crowd flowed back into the spaces from which they had been forced to retreat due to tear gas. But when necessary, the crowd flowed away from police advances like a torrential destructive force. Each police advance resulted in more businesses being smashed, looted, and burned. This meant that the police were losers regardless of whether they chose

to remain besieged or push back the crowd.

Finally, the fall of the Third Precinct demonstrates the power of ungovernability as a strategic aim and means of crowd activity. The more that a crowd can do, the harder it will be to police. Crowds can maximize their agency by increasing the number of roles thatpeople can play and by maximizing the complementary relationships

between them.

Non-violence practitioners can use their legitimacy to temporarily conceal or shield ballistics squads. Ballistics squads can draw police fire away from those practicing non-violence. Looters can help feed and

heal the crowd while simultaneously disorienting the police. In turn, those going head to head with the police can generate opportunities for looting. Light mages can provide ballistics crews with temporary opacity by blinding the police and disabling surveillance drones and cameras.Non-violence practitioners can buy time for barricaders, whose works can later alleviate the need for non-violence to secure the front line.

Here we see that an internally diverse and complex crowd is more powerful than a crowd that is homogenous. We use the term composition to name this phenomenon of maximizing complementary practical diversity. It is distinct from organization because the roles are elective, individuals can shift between them as needed or desired, and there are no leaders to assign or coordinate them. Crowds that form and fight through composition are more effective against the police not only because they tend to be more difficult to control, but also because the intelligence that animates them responds to and evolves alongside the really existing situation on the ground,

rather than according to preexisting conceptions of what a battle “ought” to look like. Not only are “compositional” crowds more likely to engage the police in battles of attrition, but they are more likely to have the fluidity that is necessary to win.

As a final remark on this, we may contrast composition with the idea of “diversity of tactics” used by the alter-globalization movement. “Diversity of tactics” was the idea that different groups at an action should use different tactical means in different times or spaces in order to work toward a shared goal. In other words, “You do you and I’ll do me,” but without any regard for how what I’m doing complements what you’re doing and vice-versa. Diversity of tactics is activist code for “tolerance.” The crowd that formed on May 27 against the Third Precinct

did not “practice the diversity of tactics,” but came together by connecting different tactics and roles to each other in a shared space-time that enabled participants to deploy each tactic as the situation required.</figcaption>

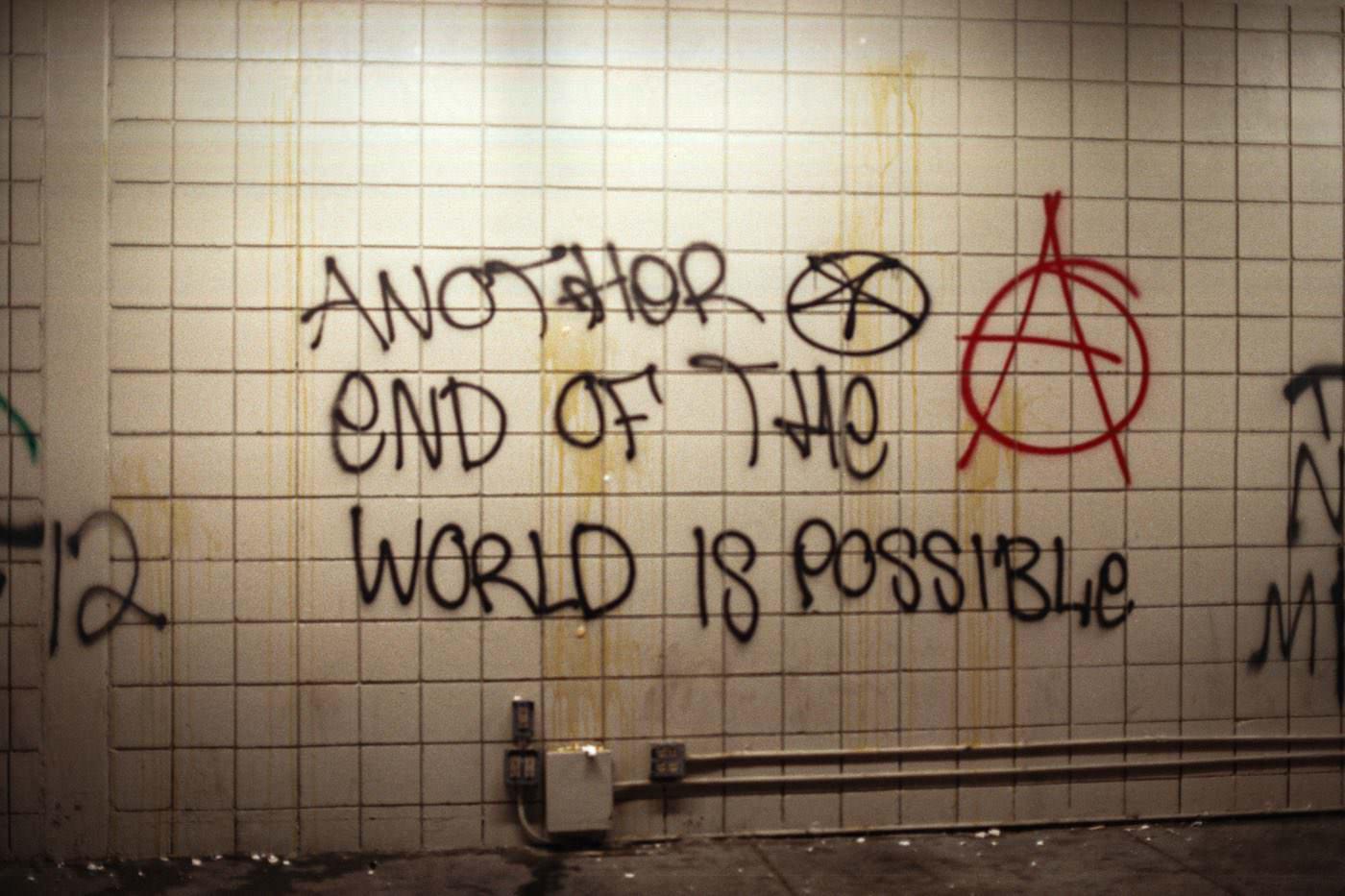

<figcaption>

May 29: Graffiti from the previous night adorns businesses.

The Ambiguity of Violence and Non-Violence on the Front Lines

We are used to seeing more confrontational tactics used to shield those practicing non-violence, as in Standing Rock and Charlottesville or in the figure of the “front-liner” in Hong Kong. However, the reversal of this relationship divided the functions of the “militant front-liner” (à la Hong Kong) across two separate roles: shielding the crowd and counter-offense. This never rose to the level ofan explicit strategy in the streets; there were no calls to “shield the throwers.” In the US context, where non-violence and its attendant innocence narratives are deeply entrenched in struggles against state racism, it is unclear if this strategy could function explicitly withoutballistics crews first taking risks to invite bloodshed upon themselves. In other words, it appears likely that the joining of ballistics tactics and non-violence in Minneapolis was made possible by atacitly shared perception of the importance of self-sacrifice in

confronting the state that forced all sides to push through their fear.

Yet this shared perception of risk only goes so far. While peaceful protesters probably viewed each other’s gestures as moral symbols against police violence, ballistics squads undoubtedly viewed those gestures differently, namely, as shields, or as materially strategic opportunities. Here again, we may highlight the power of the way that composition plays out in real situations, by pointing out how it allows the possibility that totally different understandings of the same tacticcan coexist side by side. We combine without becoming the same, we move together without understanding one another, and yet it works.

There are potential limits to dividing front-liner functions across these roles. First, it doesn’t challenge the valorization of suffering in the politics of non-violence. Second, it leaves the value of ballistic confrontation ambiguous by preventing it from coalescing in a stable role at the front of the crowd. It is undeniable that the Third Precinct would not have been taken without ballistic tactics. However, because the front line was identified with non-violence, the spatial andsymbolic importance of ballistics was implicitly secondary. This leavesus to wonder whether this has made it easier for counter-insurgency to take root in the movement through “community policing” and its corollary, the self-policing of demonstrations and movements within the bounds of non-violence.

</figcaption>

<figcaption>

May 29: Graffiti on a K-mart.

Fact-Checking: A Critical Necessity for the Movement

We believe that the biggest danger facing the current movement was already present at the Battle of the Third Precinct—namely, the danger of rumors and paranoia. We maintain that the practice of “fact checking”is crucial for the current movement to minimize confusion about the terrain and internal distrust about its own composition.

We heard a litany of rumors throughout Day Two. We were told repeatedly that riot police reinforcements were on their way to kettle us. We were warned by fleeing crowd members that the National Guard was “twenty minutes away.” A white lady pulled up alongside us in her van and screamed “THE GAS LINES IN THE BURNING AUTOZONE ARE GONNA BLOWWW!!!”All of these rumors proved to be false. As expressions of panicked anxiety, they always produced the same effect: to make the crowd second-guess their power. It was almost as if certain members of the

crowd experienced a form of vertigo in the face of the power that they nonetheless helped to forge.

It is necessary to interrupt the rumors by asking questions of those repeating them. There are simple questions that we can ask to halt the spread of fear and rumors that have the effect of weakening the crowd. “How do you know this?” “Who told you this?” “What is the source of yourinformation?” “Is this a confirmed fact?” “The evidence seems

inconclusive; what assumptions are you using to make a judgment?”

Along with rumors, there is also the problem of attributing disproportionate importance to certain features of the conflict. Going into Day Two, one of the dominant storylines was the threat of “Boogalooboys,” who had showed up the previous day. This surprised us because wedidn’t encounter them on Day One. We saw half a dozen of them on Day Two, but they had relegated themselves to the sidelines of an event that outstripped them. Despite their proclaimed sympathy with George Floyd, acouple of them later stood guard in front of a business to defend it from looters. This demonstrated not only the limit of their claimed solidarity, but also of their strategic sensibility.

Finally, we awoke on Day Three to so-called reports that either police provocateurs or outside agitators were responsible for the previous day’s destruction. Target, Cub Foods, Autozone, Wendy’s, and a half-constructed condominium high rise had all gone up in flames by the end of the night. We cannot discount the possibility that any number of hostile forces sought to smear the crowd by escalating the destruction of property. If that is true, however, it cannot be denied that their plan backfired spectacularly.

In general, the crowd looked upon these sublime fires with awe and approval. Even on the second night, when the condominium development became fully engulfed, the crowd sat across from it on 26th Avenue and rested as if gathered around a bonfire. Each structure fire contributed to the material abolition of the existing state of things and the reduction to ash became the crowd’s seal of victory. Instead of believing the rumors about provocateurs or agitators, we find it more plausible that people who have been oppressed for centuries, who are poor, and who are staring down the barrel of a Second Great Depression would rather set the world on fire than suffer the sight of its order. We interpret the structure fires as signifying that the crowd knew that the structures of the police, white supremacy, and class are based in material forces and buildings.

For this reason, we maintain that we should assess the threat posed by possible provocateurs, infiltrators, and agitators on the basis of whether their actions directly enhance or diminish the power of the crowd. We have learned that dozens of structure fires are not enough to diminish “public support” for the movement—though no one could have imagined this beforehand. However, those who filmed crowd members destroying property or breaking the law—regardless of whether they intended to inform law enforcement agencies—posed a material threat to

the crowd, because in addition to bolstering confusion and fear, they empowered the state with access to information.

</figcaption>

Postscript: Visions of the Commune

Ever since Guy Debord’s 1965 text “The Decline and Fall of the

Spectacle-Commodity Economy,” there has been a rich tradition of

memorializing the emergence of communal social life in riots. Riots

abolish capitalist social relations, which allows for new relations

between people and the things that make up their world. Here is our

evidence.

When the liquor store was opened, dozens came out

with cases of beer, which were set on the ground with swagger for

everyone to share. The crowd’s beer of choice was Corona.

We saw a man walk calmly out of the store with both

arms full of whiskey. He gave one to each person he passed as he walked

off to rejoin the fight. Some of the emptied liquor bottles on the

street were later thrown at the police.

With buildings aflame all around us, a man walked by

and said to no one in particular, “That tobacco shop used to have a

great deal on loosies… oh well. Fuck ‘em.”

We saw a woman walking a grocery cart full of Pampers

and steaks back to her house. A group that was taking a snack and water

break on the corner clapped in applause as she rolled by.

After a group opened the Autozone, people sat inside

smoking cigarettes as they watched the battle between cops and rebels

from behind the front window. One could see them pointing back and forth

between the police and elements in the crowd as they spoke and nodding

in response to each other. Were they seeing the same things we were

seeing?

We shopped for shoes in the ransacked storeroom of a

looted Foot Locker. The floor was covered wall to wall with

half-destroyed shoeboxes, tissue paper, and shoes. People called out for

sizes and types as they rummaged. We spent fifteen minutes just to find

a matching pair until we heard the din of battle and dipped.

On Day Three, the floors of the grocery stores that

had been partially burned out were covered in inches of sprinkler water

and a foul mix of food that had been thrown from the shelves. Still,

people in rain boots could be found inside combing over the remaining

goods like they were shopping for deals. Gleaners helped each other step

over dangerous objects and, again, shared their loot outside.

As the police made their retreat, a young Somali

woman dressed in traditional garb celebrated by digging up a landscaping

brick and unceremoniously heaving it through a bus stop shelter window.

Her friends—also traditionally dressed—raised their fists and danced.

A masked shirtless man skipped past the burning

Precinct and pumped his fists, shouting, “COVID IS OVER!” while twenty

feet away, some teenage girls took a group selfie. Instead of saying

“Cheese!” they said “Death to the pigs!” Lasers flashed across the

smoke-filled sky at a police helicopter overhead.

We passed a liquor store that was being looted as we

walked away from the best party on Earth. A mother and her two young

teenagers rolled up in their car and asked if there was any good booze

left. “Hell yea! Get some!” The daughter grinned and said, “Come on!

I’ll help you Mommy!” They donned their COVID masks and marched off.

A day later, before the assault on the Fifth

Precinct, there was mass looting in the Midtown neighborhood. A young

kid who couldn’t be more than seven or eight years old walked up to us

with a whiskey bottle sporting a rag coming out the top. “Y’all got a

light?” We laughed and asked, “What do you wanna hit?” He pointed to a

friendly grocery store and we asked if he could find “an enemy target.”

He immediately turned to the US Bank across the street.

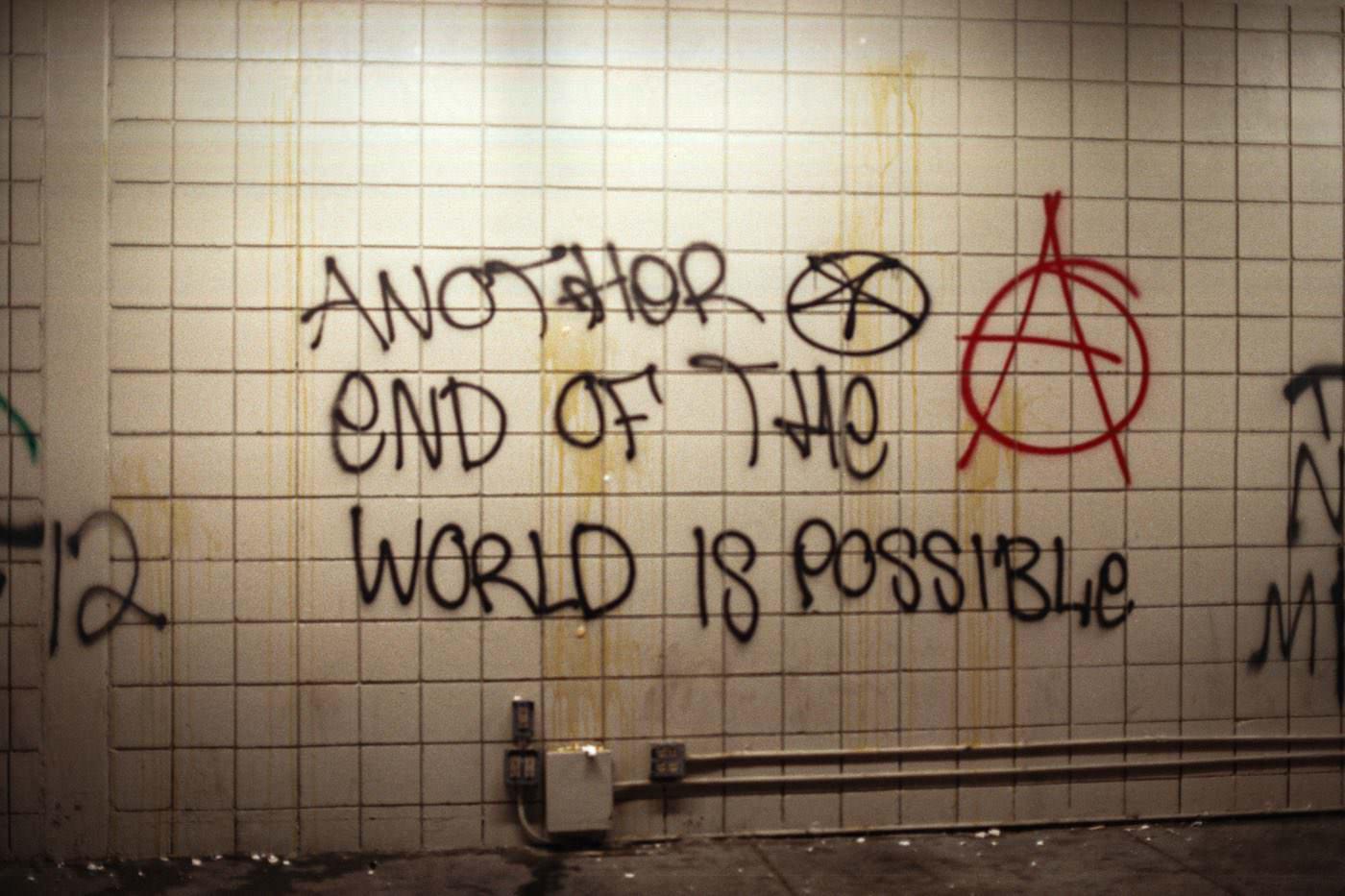

<figcaption>

“This is anarchy.”

</figcaption>

Crimethinc

Länk: https://crimethinc.com/2020/06/10/the-siege-of-the-third-precinct-in-minneapolis-an-account-and-analysis