What do anarchists mean when we talk about love? For some the word is inextricably associated with pacifism. Spiritual leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. preached love and non-violence as one and the same. “Peace and love”—together, these words have become a mantra invoked to impose passivity on those who would stand up for themselves. But does love always mean peace? Do we need to throw out the one if we disagree tactically with the other? What does it mean for us to extol love in such a violent time, when more and more people are losing faith in nonviolence? What is actually at stake in embracing or rejecting the rhetoric of love?

This word, love, has been stretched so thin as to be almost transparent, defined so variously as to be almost meaningless, distorted by abusers and advertisers alike. In the 16th century, attacking Wyncote’s translation of the Bible, Thomas More excoriated his rival for using this cheap and common word. For More, exalted religious concepts could not be properly expressed by this earthy Anglo-Saxon term. Centuries later, thousands of pop songs and billboards have further muddied the field. As a cliché and generalization, “love” feels as sticky and hollow as a punctured Valentine’s chocolate. Like this commercialized holiday, rallying under the banner of love can feel dated and suspect.

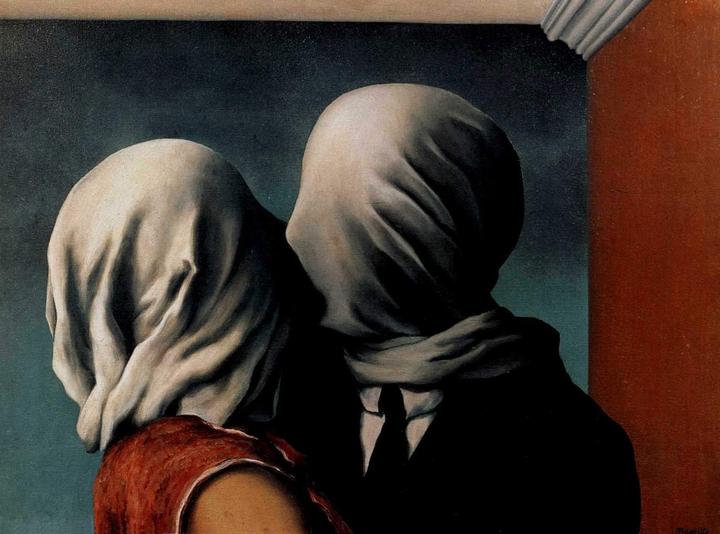

In a world of fragmented and monetized care, it can be hard to recognize what makes love a powerful force for mutual freedom. We grow up in a culture of scarcity, longing for love but pretending we don’t need it. The commodification of care into discrete roles, as parents pay others to care for their children and executives pay secretaries and sex workers for different forms of attention, causes us to think of love in transactional terms. The media reinforces this by feeding us stories that cast romantic love as the one thing that can save us; pop songs and movies justify any kind of bad behavior in pursuit of love, and we hear that love is something we need to earn and keep, like money. If we do, everything will blossom in and around us—we will have escaped the austerity that crushes all the unloved into early graves. Every romantic comedy hides the specter of our fragmented and exploitative social relations. Every misogynist assaulter, flush with entitlement, can claim love as an excuse—relying on the same logic that entitles the rich to defend their hoarded gold.

Yet we cannot do without love. Vague and corrupted though it may be, we need to understand it if we intend to practice freedom. More than a decade after bell hooks called for us to engage with love as a revolutionary practice, we are still in danger of making the same mistakes as past generations—pressing love into service as an excuse for passivity or violence, or abandoning it in favor of austere militancy that can only effect social change after the manner of the Bolsheviks.

To understand love, we can begin by understanding everything it is not. We know a lot of about the opposite of love. We see it flourishing in all forms of domination, control, and exploitation. These impulses have shaped our world for centuries, pushing colonial troops into every continent, tearing up swaths of rainforest and releasing poisons into our rivers and oceans, imprisoning and murdering countless people. Writing on the rise of totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt emphasizes that one of the necessary preconditions is an atomized society in which our connections to each other have been severed and nothing has value except as a commodity. It is easy to destroy whatever has been stripped of meaning, whatever feels alien to us, without feeling we are losing anything. It is this chasm in our social relations (which include our connections to animals and forests and mountains) that crystallizes a sense of us vs. them, the position that Arendt identifies as toxic—a fundamental precursor to wars of extermination.

In response to all this, some have valorized the insurrectionary virtues of passionate love as a disruptive force in society; others have lauded friendship as the strongest building block of the revolutionary social program. But neither of these manifestos goes into detail about how and why love fails us, and what to do when it does.

There is a fundamental difference between love as something we feel and love as something we do. As bell hooks writes, expecting love to provide us with a steady state of bliss and security “only keeps us stuck in wishful fantasy, undermining the real power of love—which is to transform us.” If we understand revolutionary love not as a feeling but a choice, a way of orienting ourselves toward the other and the world at large, we can escape the logic of love as commodity.

But if love demands that we transform ourselves, what does it ask us to become? Must we abandon militancy? Must we leave off punching Nazis? Does overcoming the “us vs. them” framework that Arendt identifies mean we must invite the police into our protests and offer an olive branch to white supremacists? In short—does practicing love mean sacrificing our power?

The pacifist who would force “peace and love” on demonstrators is second kin to the abuser who excuses his attempts to control and dominate as expressions of love. Good liberals who oppose confrontational resistance see the monster hiding in the shadows, but that monster is within themselves. Alleging that those who act directly against oppression must be poisoned by hatred, they enshrine cowardice as the proof of love. They can’t imagine fierceness and care inhabiting the same person, much less a social body that fights according to ethical principles of shared power to dismantle hierarchies. Love is not powerlessness, self-sacrifice, or keeping your hands clean. Love is courage. This far, if no further, we must agree with a certain doctor who acknowledged, in the least ridiculous moment of his life, that “the revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.”

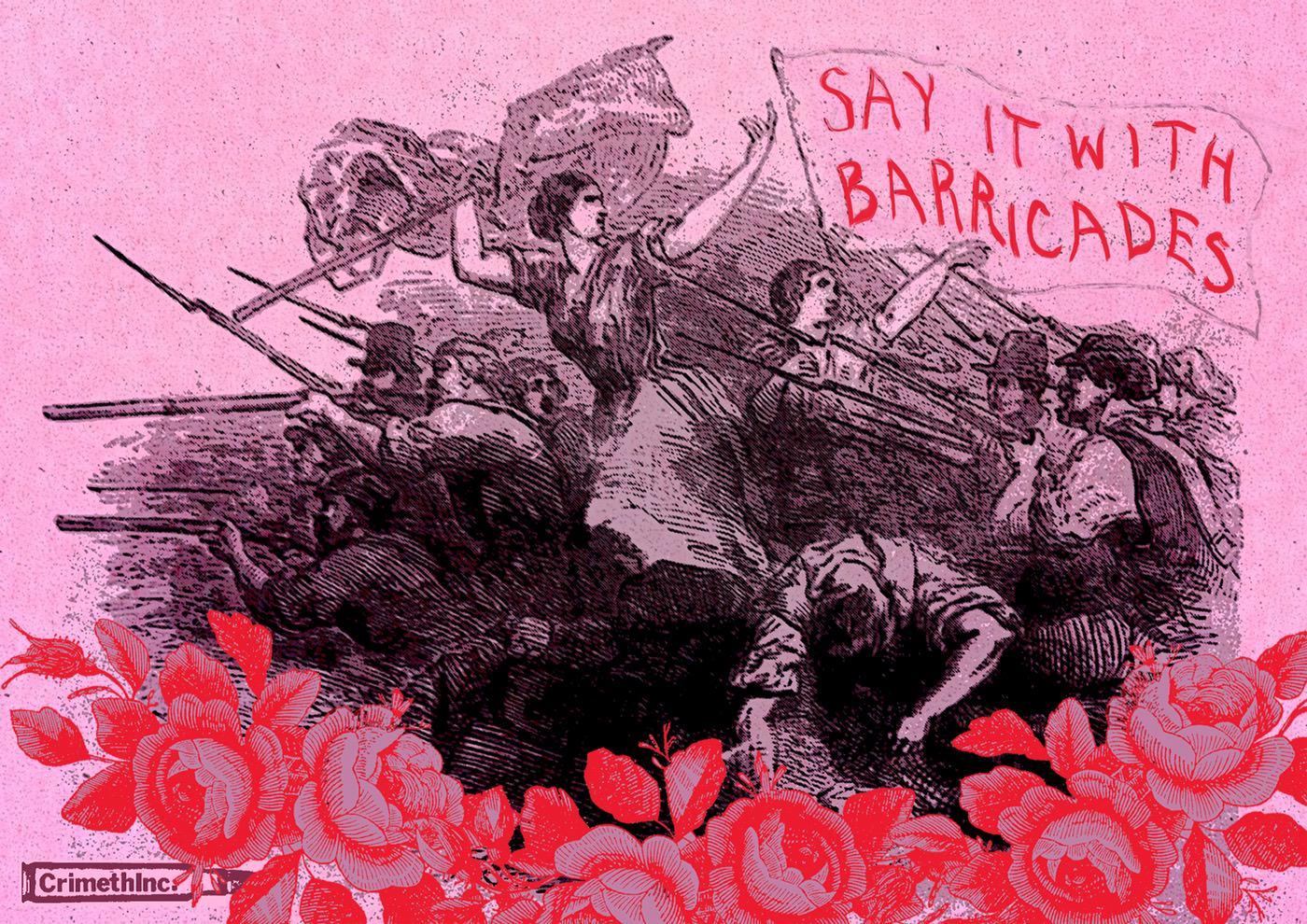

What does it mean to be guided by such feelings, then? Love is a quality of attention, a sensitivity to the world and everything that is possible in it. When we fight on the basis of what we love, rather than in service of ideology or cowardice, we open ourselves to serve as a channel through which everything beautiful in the world can defend itself. To choose love is to choose to keep feeling the blows when others are under attack—everyone facing felony charges, everyone threatened with deportation, everyone facing water cannons at Standing Rock, all the rivers and animals and plants that sustain us despite all the violence inflicted upon them. Love is not reducible to peace. If you mean it, say it with barricades.

“Love comes with a knife, not some shy question, and not with fears for its reputation!” Jalaluddin Rumi

</figcaption>Crimethinc

Länk: https://crimethinc.com/2017/02/14/say-it-with-barricades-the-difference-between-peace-and-love