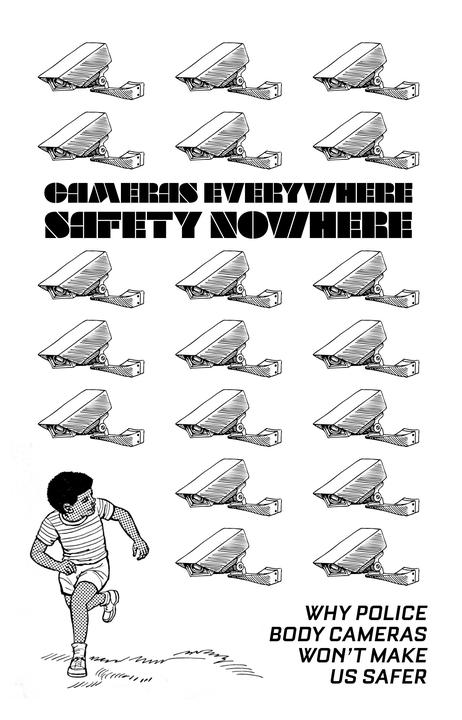

We know that police violence is a real problem in the US, and it makes sense that people are strategizing ways to protect themselves and their loved ones from being assaulted or murdered by the police. Many who are concerned about this issue have begun advocating for police to wear video cameras on their uniforms. The idea is that cameras will prevent police violence, or at least hold officers accountable after the fact. Groups like Campaign Zero (a reformist Black Lives Matter offshoot) and the American Civil Liberties Union are advocating this measure, and even police departments themselves, after initial resistance, have signed on. But the idea that more cameras translates to better accountability (however we define this) relies on a faulty premise. Police get away with murder not because we don’t see it, but because they’re part of a larger system that tells them it’s reasonable to kill people. From lawmakers, judges, and prosecutors to juries, citizens, and the media, every level of society uncritically supports and transmits the police point of view. In this atmosphere, police can murder with no fear of repercussions.

Advocates of police-worn body cameras, as well as advocates of bystanders filming the police, constantly claim that cameras act as equalizers between police and people, that they are tools for accountability. But there is very little evidence to support this. Many assume visibility will bring accountability—but what does accountability even look like when it comes to police violence? If charges are all that police reformers would demand, where do they go when those charges end in verdicts of innocence or mistrial, as they almost inevitably do? Do they just go home and revel in the process of the justice system? Or are there other options situated outside official channels? The reality is that we don’t have a visibility problem but a political problem. The only “accountability” we see seems to be in occasional monetary settlements (paid by taxpayers). These settlements don’t hold officers accountable, or prevent future assaults and murders.

Though initially hesitant to adopt body cameras, police departments and officers quickly changed their tune as they realized that cameras benefit them far more than they benefit the general public under surveillance. We now have 4000 police departments in the US that employ body cameras, including the two largest, Chicago PD and NYPD, no strangers to inflicting violence on people and getting away with it. The largest marketer of officer-worn body cams, the leader in a $1 billion per year industry, is Taser Inc. After creating their namesake product, which was used to kill at least 500 people between 2001 and 2012, Taser started adding cameras to their stun guns in 2006, and introduced the body-worn camera in 2008. Since this introduction, their stock value has risen ten times higher. This was in no small part helped by grants from Obama’s Justice Department, which spent $19.3 million to purchase 50,000 body cameras for law enforcement agencies. Taser has since introduced a cloud storage service marketed to police forces (yes, a privately owned evidence storage service), proposed manufacturing drones with stun guns (and of course, cameras) attached to them, and recently bought the company Dextro, which has developed software to identify and index faces and specific objects.

<figcaption>

<figcaption>“Visibility is a Trap” – Michel Foucault

</figcaption></figure>The other night I was standing on a subway platform and looked up at the digital sign that announces when the next train is coming. But at that moment the sign was delivering a different message: “Surveillance cameras are no guarantee against criminal activity.” It fascinated me that the very institution installing surveillance cameras would admit this, while so many people on the receiving end of that surveillance are blind to this idea as they advocate for police body cameras.

Far too many believe that people “behave” while others are watching. What rarely gets discussed is that there is no way to “behave” that will seem appropriate to everyone. If police believe, as has been shown that their actions are justified, and that their superiors, the legal system, and the population as a whole approve of their actions, no matter how deplorable a few of us find them, they will continue to “behave” the way they have since their inception, despite (and potentially because of) the cameras watching.

Police don’t fear legal or extralegal repercussions because they don’t have to.

There are several reasons police that kill so rarely get charged with murder. First, laws and court decisions require an incredibly high burden of proof that an officer acted without “reasonableness.” Washington State has the highest barriers to bringing charges against police. Because of the wording of laws concerning police use of deadly force, only one Washington cop was charged with killing someone during the years 2005 through 2014, despite police having killed 213 people. That one officer was found innocent, despite having shot a man in the back. Beyond legal mandates for proof, police are the ones who investigate officers that kill. A notoriously self-protective bunch, they even have a nickname for their code to stick up for each other at all costs. Prosecutors come next. They depend on the police on a day-to-day basis to be able to, well, prosecute. They have a heap of motivation to keep the police officers they work with happy. Below this we have judges and juries who, the great majority of the time, believe police officers over those who would speak against them. Finally we have the media, who more often than not parrot official police opinions without question, and the consumers of this media that make up the juries. Juries are also often comprised of those who can afford to take time off work, while those killed by police are most often from lower economic classes, hardly “peers” to those serving on the juries.

So far as I can find, in the nine years that police body cameras have been in use, there is only one case of police facing charges after they murdered someone while wearing cameras. On March 16, 2014 in Albuquerque, New Mexico, James Boyd was camping in a city park when a citizen called police to report him. Eventually nineteen officers responded to the call, including two with dogs and a sniper. Boyd was known to have schizophrenia and was carrying two knives for protection. After a three-hour standoff, two of the officers, Keith Sandy and Dominique Perez, shot Boyd a total of six times. On October 11, 2016, the officers’ trial was declared a mistrial, as the jury was deadlocked with nine believing them to be innocent and three finding them guilty. Officer Sandy’s and Perez’ body cams did not prevent them from shooting Boyd, nor did the video they captured help hold them accountable for his death. The prosecutor claimed that video “cannot lie,” yet nine jurors saw the video of a man in mental distress, surrounded by nineteen cops, get shot six times and decided those cops acted reasonably. Video might not lie, but it isn’t necessarily neutral. It shows a point of view, and is subject to interpretation. As of this writing, Keith Sandy has retired, and Dominique Perez is set to get his job back. As so often happens in these cases, charges against the cops resulted not in any accountability for the officers, or even the department, but in a $5 million settlement paid by the taxpayers of the city of Albuquerque to the family of James Boyd.

While the prevalence of videos documenting murders by police has certainly risen with the popularity of video-equipped cellphones, we have yet to see a rise in “accountability.” More cops aren’t being charged with murder, more cops aren’t being convicted of murder, and numbers of murders by police aren’t going down. Eric Garner’s murder at the hands of NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo was documented by a bystander, but this video didn’t save Garner’s life or lead to any accountability for Pantaleo (though he was later docked two vacation days for an illegal stop-and-frisk that occurred two years before he killed Garner).

“The Whole World Is Watching!” is a phrase countless crowds on the receiving end of police violence have chanted. Leaving aside the hyperbole, we have to ask ourselves: So what? Journalist and activist Don Rose claimed to have coined this phrase when he said, “…tell them the whole world is watching and they’ll never get away with it again.”

But history shows otherwise. Protesters being attacked by police most famously delivered the chant outside of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968. Despite Rose’s claim, Chicago’s mayor at the time claimed he received 135,000 letters of support. Not a single officer was punished for the violence. Even when almost the whole world is watching, as in famous cases like the Rodney King assault, that is still no guarantee the cops responsible will be punished (a jury acquitted the officers who assaulted King). From the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle to Occupy Wall Street, no matter how many times protesters beat this dead horse of a chant, police have continued to bring down blows on their heads, with no substantial repercussions and no end to the violence.

The whole world may be watching, but do they care?

</figcaption></figure>Advocates of police body cams often tout a study of the Rialto Police Department, which began using body cams (on some officers) in 2012. The study showed a large drop in complaints against the police force. Far too many media outlets and advocacy groups have touted this drop in complaints as a positive result, attributing it solely to the use of body cams. What few acknowledge is that the study author, Tony Farrar, had a conflict of interest as Rialto’s chief of police. Farrar had been brought in to save a failing police department whose use of force was excessive enough to threaten their very disbanding—he had strong motivation to decrease his officers’ use of force, with or without body cameras. Another angle media ignored is that a drop in complaints doesn’t imply a drop in reasons to complain. Just like body cameras themselves, a drop in complaints will always benefit the police, but won’t necessarily benefit the rest of us. People may still have valid reasons to complain, but fear of possible repercussions restrains them. This fear may be magnified as body cameras represent yet another form of surveillance. In this case, body cameras increase an atmosphere of intimidation, being far more likely to pacify the general population than it is to pacify the armed killers wearing them. Whatever a body camera records, its perspective always supports the logic of the state and its foot soldiers.

Far too many people assume that video footage is itself neutral. They think anyone who watches a video of police killing someone can only react with outrage, or at least a clear sense of injustice. But one has only to spend a few minutes reading comments on news articles with embedded videos of police killings to see that a substantial number of people react with thoughts such as “the cop was in danger,” “s/he shouldn’t have run from the police,” etc.<sup>1</sup> People’s existing thoughts and opinions, and not least their politics, color how they interpret video footage. We have no reason to believe that police oversight boards, prosecutors, judges, or juries will look at these videos and see the same thing that victims and critics of the police see. It is dangerously naïve to assume that accountability will follow a “reform” such as body cameras, when all the evidence says otherwise. The point of view of the police is nearly always privileged over those who would criticize them in the eyes of judges, juries, and the rest of the public. Because police body cams quite literally show the point of view of the police (an aspect that Taser specifically mentions in their marketing materials), these videos offer a perspective in which it is easy for viewers to place themselves in the officers’ shoes, and sympathize with the positions and actions taken by the cop wearing the camera.

As a child of 1980s television, I learned from G. I. Joe that knowing is half the battle. But one thing far too many miss is that knowing is ONLY half the battle—the other half is action. We can depend on technologies to save us no more than we can depend on the court system, a court system that is part and parcel of the system of policing.

Anywhere you travel these days you can see signs that read, “if you see something, say something.” Many would-be police reformists (such as The Cato Institute’s National Police Misconduct Reporting Project) have extended this to: “if you see something, film something.” But this injunction relies on the idea that merely bearing witness is enough—that in documenting an atrocity you have fulfilled your moral obligation. It presumes that after you’ve filmed the incident, the wheels of the system will turn and eventually justice will prevail … which we’ve seen is mere wishful thinking. What if, instead, we say “if you see something, DO something?” What if every time a police officer intends to harm someone, they have to fear that a bystander will not merely bear witness, but attempt to stop them BEFORE they can act—before they can traumatize or kill someone? What would it take to make this reality?

Those who advocate for police body cameras want to believe in accountability through official channels, and hope that visibility will protect us from the very real threat the increasingly militarized police present. Sadly, these tools haven’t worked, and are contributing to more broad forms of surveillance that affect all of us. We don’t need more thorough information about what the police are doing. We need to stop them from doing what they do. We’re not looking for transparency, or accountability. We’re looking for a world without police. We want to go beyond the demands for accountability, to build a world that not only doesn’t need police but is inhospitable to those who would police us.

Ben Brucato:

crimethinc