On Friday, May 3, 1968, several hundred radical students stared down a contingent of fascists outside the Sorbonne, in Paris. The day before, the neo-fascist group Occident torched the offices of a leftist student organization, leaving behind their call sign, the Celtic Cross. In response, radical students called for a demonstration against “fascism and terror,” steeling themselves for a fight.

Brawls between radicals and fascists had become a common feature of the Parisian political scene since the Algerian War, when fascists turned to terrorism, assassination, and bombings in a last-ditch effort to prevent Algerian independence, demolish the left, and seize state power. After the war, paramilitary groups like Occident continued to wage war on the left. In this context, many student radicals began their political education in antifascist organizing, where they learned how to fight fascists in the streets, confront the police, and organize swift, militant actions. As one radical explained, “I was antifascist. That was how I was socialized. Others wielded the dialectic – I wielded the matraque.”

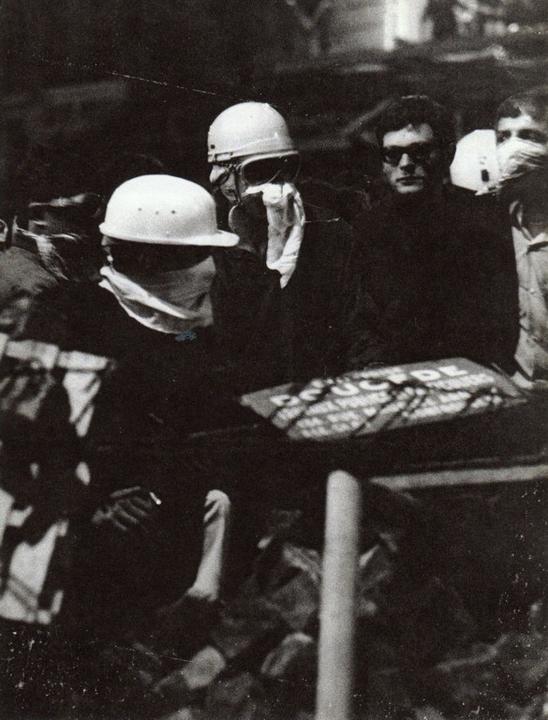

The radical youth groups of the 1960s developed paramilitary wings known as the service d’ordre (SO). As its name suggests, the SO took responsibility for maintaining general order. They acted as parade marshals during demonstrations, protected rallies and meetings from raids, defended militants hawking newspapers from fascist attacks, and later handled security at occupations. But the SO also played an offensive role, disrupting lectures during student strikes, storming fascist meetings, and confronting police during demonstrations. For those in the movement, there was no contradiction between these functions, so long as the SO answered to the larger struggle.

That Friday, both sides came prepared. When Occident thugs marched towards the university, sporting helmets, clubs, and smoke bombs, radicals fastened their helmets and smashed furniture to fashion weapons for the inevitable melee. Panicking, the chancellor called the police, who made matters worse by raiding the demonstration and making indiscriminate arrests. Students quickly retaliated, surrounding police vans, ripping up cobblestones, and throwing missiles at police.

The were 574 arrests that day. Students across Paris were radicalized by the crackdown, and took to the streets demanding that the police liberate their comrades. Protests climaxed a week later, on May 10, when radical youth, led by the battle-hardened SO, fought police into the night. Radicals cut down trees and overturned cars to erect barricades, stretched wires across the streets, rolled automobiles into police lines, set fires to halt police advances, and unleashed salvos of cobblestones. When the plumes of tear gas finally cleared, 200 cars lay in ruins, at least 400 were injured, and over 500 arrested.

Remarkably, despite the vandalism, violence, and property destruction, polls indicated that 80 percent of Parisians supported the youths. In fact, residents of the Latin Quarter provided protesters with food, water, material for barricades, and refuge from police. On May 13, the unions called a strike. Students occupied the university, factory workers followed suit, and by the end of the month, some nine million workers were on strike. As life in the capital ground to a halt, President de Gaulle left the country to consult with the army. Though de Gaulle soon reasserted control, the May events overturned French society. Factories became ungovernable for over a decade, diverse social movements proliferated across the country, and de Gaulle himself was forced out of office in 1969.

It’s astonishing to see, then, the reaction of the liberal intelligentsia to the return of the “black bloc” today. Some critics, like Erica Chenoweth, claim that “history” allegedly proves that “black bloc tactics” are ineffective. To begin with, accounts like these erroneously conflate militant street-fighting with armed struggles against dictatorships, misrepresenting the black bloc as a militia or guerrilla force, rather than a specific tactic. Even worse, they’re historically inaccurate. There’s little doubt among historians that militant street-fighting played a crucial, catalyzing role in 1960s France. There’s also agreement that the tactic proved effective in many other struggles – for an example closer to home, consider the Detroit uprising of 1967. Rather than ending in chaos, the riots not only radicalized unions, but actually generated long-lasting and durable organizations like the League of Revolutionary Black Workers.

But let’s not make the opposite error as Chenoweth. The example of May ‘68 does not suggest that street-fighting will automatically call into being mass movements of the kind that radically overturned French society in the 1960s and 1970s. The confrontational tactics of radical youth before and during May 1968 detonated a highly combustible conjuncture, and the exact political sequence of the May events can never be repeated.

“History,” then, does not provide us with models to mechanically follow or avoid. If the history of militant confrontation shows us anything, it’s that black bloc tactics may work in some cases and not in others: effectiveness depends entirely on the conjuncture at hand. Evocations of the past might shed light on a time when something like the black bloc did play an important role in social movements, but can’t tell us whether the black bloc is appropriate today. Only a concrete analysis of our concrete situation can determine what role, if any, the black bloc can play in today’s movements. While many have rightly questioned the bloc’s overall effectiveness over the past decade or so, we are now in an objectively different historical conjuncture, which should force us to reconsider the potential role of the black bloc.

New Conjuncture

As I have argued elsewhere, the black bloc represented a specific tactic that once enjoyed a valuable place within the strategy of a certain constellation of movements. But over the course of the 1980s and 1990s, these movements collapsed, repression heightened, and radical spaces were restructured, undermining the social bases that grounded black bloc tactics. The bloc managed to live on as a kind of “floating tactic,” but survival came at a cost. Without a broader strategy, partisans of the bloc found themselves compelled to continually reproduce this single tactic in the hopes of spontaneously resurrecting the strategy that once gave it meaning, trapping themselves in a bad infinity of spectacular actions. Separated from mass organs, its members tended to take on a distinct cultural identity, sometimes in outright opposition to movements. Throughout the 2000s, some black bloc militants derided other demonstrators for holding them back, while less confrontational activists denounced the bloc for irresponsible adventurism. It’s from this period that the bloc’s reputation dates.

But the dawning of the Trump administration has changed the game. By unleashing a massive assault on all sectors of the working class, his presidency has raised questions about security, personal safety, and bodily autonomy. Trump’s unilateral imposition of racist immigration policies has already thrown the lives of immigrants into disarray. Future actions will further imperil the lives of the undocumented. If passed, the Republican’s nationwide right-to-work bill would gut unions, leaving countless American workers even more vulnerable than they already are. Meanwhile, Trump’s foray into “healthcare reform” could leave twenty million Americans uninsured, potentially resulting in 43,956 deaths annually. Hate crimes have already spiked, as emboldened fascists have tagged swastikas in cities across the country, sent death threats to synagogues and mosques, and verbally and physically harassed minorities. Just two weeks ago a Tump supporter shot a protester at a Milo Yiannopoulos event in Seattle – the victim’s right to free speech saw none of the defense from civil libertarians that Richard Spencer was granted for a non-lethal punch. In this context, it’s worth reconsidering the role that militant confrontation, and self-defense, might play in protecting collective movements.

There’s also evidence that the idea of confrontation is gaining wider acceptance. Many of those organizers who have not previously adopted black bloc tactics are growing far more receptive, and in some places are seeking alliances with those who use them. Despite the controversy surrounding the event, it seems many Berkeley students supported the militant tactics that prevented Milo from speaking at Berkeley, where he intended to launch a campaign against sanctuary campuses, and may have planned to reveal the names of undocumented students. “My campus did nothing to stand between my undocumented community and the hateful hands of radicalized white men — the AntiFas did,” an undocumented student wrote of the Milo event. “A peaceful protest was not going to cancel that event, just like numerous letters from faculty, staff, Free Speech Movement veterans and even donors did not cancel the event. Only the destruction of glass and shooting of fireworks did that.”

There’s even a growing mainstream interest in the black bloc. Within hours, the video of Richard Spencer getting punched in the face received nearly a million views, and was set to music from “Born in the U.S.A.” to “The Boys Are Back in Town.” The black bloc is now discussed at the dinner table, featured on cable television, and addressed on the front page of the New York Times, challenging some mainstream liberals like Sarah Silverman to rethink their assumptions. This changing attitude is likely a reflection of the radicalizing political situation. Animated by Trump, hundreds of thousands of Americans who never joined a protest before this election are now sacrificing their free time for political meetings, marching against traffic, shutting down airports, getting trained as organizers, and even contemplating a general strike. Many are coming to feel that the violence of a broken window pales in comparison to the violence of Trump’s administration. In fact, it’s precisely this surprising openness to black bloc tactics that has sent critics into such a delirious state.

At the same time, black bloc militants recognize the need to find ways to organically integrate street-fighting within a whole ecosystem of struggles. Let’s not forget that in Berkeley, the bloc’s actions were only one aspect of a broader campaign that included publishing op-eds, buying out tickets, working with faculty to pressure the administration into canceling the event, organizing through the UAW, contacting local politicians, reaching out to different communities in the area, and holding public meetings.

The black bloc militants I’ve spoken to at recent demonstrations in Philadelphia have stressed the importance of working with larger mobilizations, not against them. That means transforming the bloc from an identity to an integrated tactic. The way forward, then, is to creatively articulate street-fighting not only with a wider range of tactics, but with wider mass movements, which will likely mean putting the bloc to a range of uses, as French radicals in the 1960s did with the service d’ordre.

During Trump’s inauguration, black bloc tactics helped Black Lives Matter activists shut down a checkpoint, chasing away neo-Nazis. What other uses can the bloc serve today? Shutting down airports? Protecting abortion clinics? Helping to stop deportation raids? Defending the autonomous survival programs we’ll need to develop in the coming years?

Challenges

The question, then, is whether Trump’s presidency has created the conditions to restore the black bloc to its historical function as an integral element of mass struggles, rather than as a floating tactic. It seems the possibility exists, but making this encounter take hold will no doubt present many challenges.

First, there’s the hypocrisy of American conventional wisdom on violence. During May ‘68, the Parisian public thought little of the dozens of cars that went up in flames. The police, whom the majority disrespected, were clearly in the wrong. In contrast, although it’s clear that thousands of Americans are coming to rethink militant confrontation in the streets, the ideology of law and order remains strong. Even among some who oppose Trump, the police are often presumed innocent, and their victims guilty. For the black bloc to find a firm place in today’s movements, this ideological deference to legal authority has to change.

This is not at all to say, as the liberals do, that this attitude is so ingrained that we should throw our hands in the air and police our movements so they appeal to liberal sensibilities. If there’s one thing we’ve learned this past year, it’s that the people’s attitudes can change rapidly. We can expect Trump to do some of this work for us. But we can also make an effort to wage a fierce campaign of political education, especially within the mass demonstrations drawing in tens of thousands a week, that insists we approach confrontation not through moralistic judgement but tactical consideration.

Second, there’s the challenge of formalizing the link between the black bloc and other struggles. To be effective, the black bloc requires a certain degree of autonomy, especially given the legal risks of confrontation. On the other hand, if the bloc is to amplify movements, rather than work at cross-purposes, it must be transparent and accountable. In the past, the balance was achieved through formal organizational unity. The service d’ordre, for example, existed within, and took general direction from, a larger organization. In this way, those engaged in bloc tactics and those involved with other actions could coordinate their efforts to achieve maximum effectiveness. To make the link work today, we need to find ways to recreate this formalized relationship, which means inventing new forms of unity and building collective organizations. In fact, in the current context, the very question of unity makes little sense without organization.

Lastly, and most importantly, if this reunification is to work, we need a strategy. The black bloc, after all, represents only a tactic. While Trump’s presidency may have created a new need for militant confrontation, the larger strategic questions that can give such a tactic meaning remain open. How can we collectively articulate diverse social forces into a lasting political unity that respects their different needs, interests, and desires? What forms of organized self-activity will resonate with the particular composition of the U.S. working classes? In what ways can the anti-Trump resistance transition into a positive movement for radical social change, beyond capitalism and the state? Only by thinking through these strategic questions can we really determine the place of the black bloc, and not the other way around.

Widening our Horizons

On May 7, 1968, members of the UJCml, one of the radical student organizations of the time, met at the École normale supérieure to discuss the student revolts. Robert Linhart, the group’s undisputed leader, remained convinced that the entire affair was a ruse. Fastened to a crude workerism, Linhart argued that rebellious students could not possibly lead the revolution. In fact, their puerile street-fighting was not only a distraction, but played right into the hands of the bourgeoisie by keeping them trapped in the Latin Quarter, away from the workers. As their flier, And Now to the Factories!, explained, everyone should “leave bourgeois neighborhoods where we have nothing to do,” and “go to the factories and popular neighborhoods to unite with the workers,” the only class who could make the revolution.

Yet the order to ignore the student demonstrations did not sit well with UJCml activists who watched as the Latin Quarter went up in flames. “Robert,” Linhart’s wife declared, “the students are fighting outside. It’s foolish to stay here, behind closed doors. It’s time to join in … The proletariat wants to join the demonstrations and, following the students’ example, to go on strike!” Linhart, however, refused to budge. Trapped in rigid models, refusing to assess the novelty of the situation at hand, the UJCml missed the opening acts of May ‘68.

It’s not 1968, and never will be again. The May events don’t give us a model to follow. On the contrary, they reveal the need to treat models and received ideas with caution, to remain politically flexible in the face of a new and unfamiliar situation. Indeed, this is the lesson French militants drew after the energies of the insurrectional period subsided. Many attempted to configure a historically adequate, effective set of political practices, through inquiry and “action committees,” to set up relays between the struggles of workers, students, immigrants, and the still-substantial French peasantry. We have to recognize that we’re in a radically different and quite unstable historical conjuncture. The playbook can only take us so far. We have to take inspiration from the struggles around us, whatever their contradictions, and broaden our imagination.

It may be that the black bloc’s time is over, that it remains completely inadequate to our present conjuncture. But it may also be the case that we can find ways to reintegrate the bloc into today’s struggles, which might ultimately make our movements even stronger. We will get nowhere by indulging in knee-jerk denunciations based in moralism, dubious appeals to the authority of history, or fixed ideas about what struggles ought to look like, as the real struggles rage outside. We have to begin with a concrete analysis of the concrete situation to see what kind of political experiments we need today, making sure we don’t miss the possibilities of unprecedented events. Instead of drawing conclusions from behind closed doors, we should base our strategy on what’s happening in the streets.

Viewpoint Magazine