2017-10-17

6 underrated Marxists who don't get enough love

It's a sad fact that many of the most radical

Marxists, whose participation in working class struggle and ideas

challenged not only capitalist society but also the social democratic

and Leninist tendencies in the workers' movement tend to get ignored by

anarchists and Marxists alike.

In this post we look at individuals who participated in working class movements from the 1918 German revolution to the 1945 Saigon Commune

to wildcat strikes in car factories in Detroit and contributed an

understanding of the events of their time that we can learn from today.

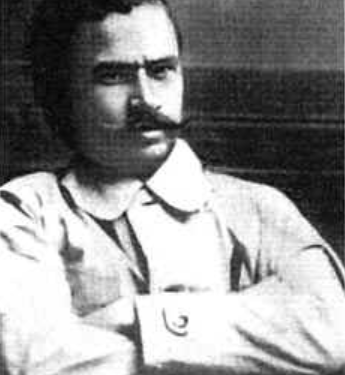

A participant in both 1905 and 1917 Revolutions as well as the Bolshevik underground, Miasnikov

gained a reputation as a hardened working-class militant, doing seven

years hard labour in Siberia for his activism and executing the Tsar's

brother himself. A member of the left communist fraction in the

Bolshevik Party, his expulsion led to the formation of the Workers Group and eventually a complete break with the Bolshevik ideology.

While still a member, he criticised the leadership for its

bureaucratisation and repression of working-class dissent both within

the party and wider society, saying, in a letter to Lenin: "while you

raise your hand against the capitalist, you deal a blow to the worker."

Miasnikov's view was that the Soviets should take over the running of

society, as they had been set up during the revolution through the mass

participation of the workers themselves. The party leadership and other

'left oppositions' within the Bolsheviks, were focused on the power of

the party and the trade unions rather than the class itself.

Expelled from the party, he set up the 'Workers Group' and published a

manifesto critical of the Bolshevik regime from Germany. In September

1923, during a strike wave in Russia, he was lured back on the pretense

he would not be interfered with, was immediately arrested on arrival and

exiled to Armenia, before escaping to France where he wrote 'The Latest Deception',

elaborating his theory of state-capitalism in the USSR, arguing it had

to be overthrown and replaced with soviet democracy. In 1945 he returned

to the USSR from France on a visa, but was arrested within a month by

secret police, and executed 16th November 1945.

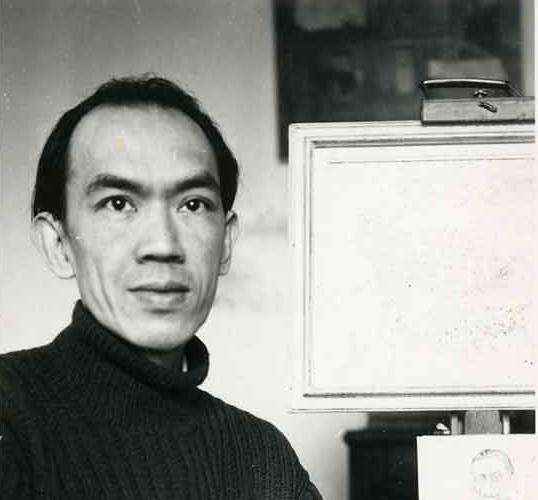

The life of Vietnamese Marxist Ngo Van Xuyet

takes us from the anti-colonial struggle in Vietnam, where he found

himself in conflict not only with the French authorities but also Ho Chi

Minh's Stalinist forces of 'national liberation', to the factories of

Paris during the 1968 uprising.

Starting work in Saigon's metal factories aged 14, Ngo joined the

Vietnamese Trotskyist movement five years later. Involved in various

struggles against French colonial rule, he was eventually imprisoned and

tortured for organising a strike at his factory. He organised hunger

strikes with other prisoners and later participated in the 1945 Saigon Commune

before leaving Vietnam in 1948 to escape both French colonial

persecution and possible assassination by Ho Chi Minh's forces (as

happened to several of his comrades).

Resettled in Paris and working in a factory making railway signals,

he broke with Trotskyism and the Leninist conception of the party,

mixing with anarchists, council communists and ultra-left Marxists. An

active workplace militant, he was involved in the Paris Metalworkers'

Liaison Committee and a participant in France's May 1968 revolt, writing

an excellent first-hand account from the point of view of a rank-and-file factory worker angry at the actions of the French Communist Party and CGT union to contain the rebellion.

Upon his retirement, Ngo dedicated himself to recording the struggles of the Vietnamese working class and peasantry against colonialism and independent from Ho Chi Minh's Stalinist national liberation movement as well as instances where the latter used violence against other sections of the Vietnamese revolutionary movement.

He also wrote an excellent autobiography documenting his amazing life

as a working-class militant across two continents called In the crossfire: adventures of a Vietnamese revolutionary.

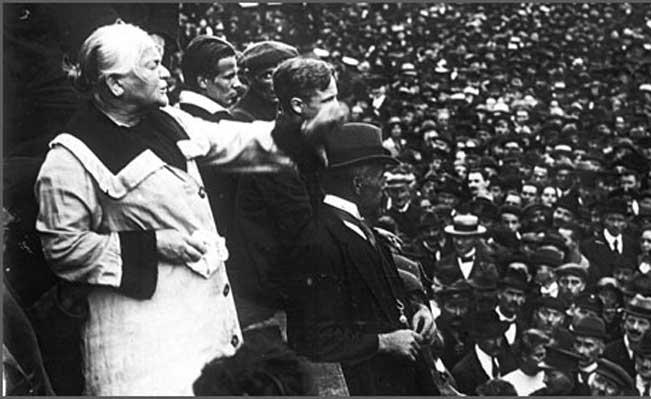

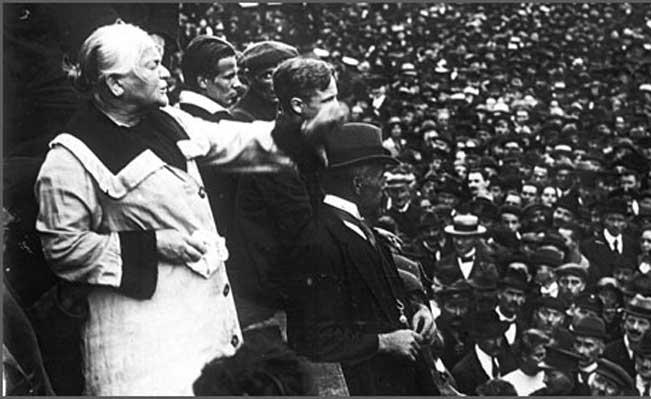

Clara Zetkin

was a central figure in the left-wing of German Social Democracy,

active in the Bookbinders and Tailors & Seamstresses Unions in

Stuttgart when it was illegal for women to be union members.

Zetkin broke with the mainstream of the Social Democratic Party in

1914 when she took a consistent anti-war position. She joined the

Spartacists with Rosa Luxemburg

and Karl Liebknecht, then founded the Communist Party of Germany with

them in 1918. While she completely broke with the Social Democratic

Party, she did not make the full break from social democracy to council

communism like the KAPD or AAUD-E, and lived in Russia from 1924 until her death in 1933.

Zetkin's work is notable for some of the earliest applications of

Marx's work in Capital to the women's question. She analysed the entry

of women and children into the labour market, and the development of

automation as undermining the wages and working conditions of both men

and the working class as a whole. However, she completely rejected male

chauvinist attempts to restrict the participation of women in the

workplace to preserve high wages, instead pointing out that the only

solution to a shorter working day and the full liberation of both men

and women was the overthrow of capitalism:

Just as the workers are subjugated by the capitalists,

women are subjugated by men and they will continue to be in that

position as long as they are not economically independent.[..] Women

workers are totally convinced that the question of the emancipation of

women is not an isolated one but rather constitutes a part of the great

social question. They know very clearly that this question in today's

society cannot be solved without a basic transformation of society.

[...] The capitalist system alone must be blamed for the fact that

women's work has the opposite result of its natural tendency; it results

in a longer work day instead of a considerably shorter one. [...] If

one demands the abolition or limitation of women's work because of the

competition it creates, one might just as well use the same logic and

abolish machines in order to demand the recreation of the medieval guild

system which determined the exact number of workers that were to be

employed in each type of work.

For the liberation of women (1889)

Unsurprisingly, her class analysis of women's issues meant she was

scathing in her criticisms of the bourgeios suffragettes, describing in

her 1903 text, 'What Women Owe to Karl Marx', that the 'sisterhood'

which "supposedly wraps a unifying ribbon around bourgeois ladies and

female proletarians" as bursting "like so many scintillating soap

bubbles."

Her account of discussions with Lenin

about the women's question show very effectively the limitations of

Lenin's politics in this regard, as he requested German communists focus

away from sex worker organising and 'the sex question' towards pure

party building.

In 1923, Zetkin penned an analysis of the rise of Mussolini in Italy

and the nascent fascist movement in Germany. In passages which

anticipate Dauvé's work

by half a century, she identifies the fascist movement as the last

resort of the bourgeiosie to maintain capitalist relations via open

violence against the working class and the consequence of the failure of

proletarian revolutions internationally, against the reformist

socialists who had blamed revolutionary attempts for the rise of

fascism.

The proletariat must have a well organised apparatus of

self-defence. Whenever Fascism uses violence, it must be met with

proletarian violence. I do not mean by this individual terrorist acts,

but the violence of the organised revolutionary class struggle of the

proletariat.

(Fascism, 1923)

Martin Glaberman's great skill was presenting complex ideas in ways which relate to people's everyday experiences.

A worker in Detroit's car factories from the early 1940s to the

1960s, Glaberman started his political life as a Trotskyist, joining the

Johnson-Forrest Tendency, founded by (amongst others) legendary

Trinidadian Marxist CLR James.

By the 1950s, they had broken with Trotskyism, taking a more critical

position on the USSR and rejecting the need for a vanguard party to

seize power on behalf of the working class, and formed the

Correspondence Publishing Committee. Glaberman remained associated with

CLR James through the '60s via the Facing Reality Group in Detroit.

Glaberman's work is consistently rooted in the concrete experiences

of the working class: the relationship of union officials to rank and

file workers on the shopfloor, the relative strength of factories

dependent on their position in the production process. But his work is

never 'dumbed down'; rather, his down-to-earth explanations of complex

Marxist concepts lead seamlessly into practical politics. For instance,

in his article Unions and workers: limitations and possibilities, he says,

Quote:

Consider these two units of time: 36

seconds, the rest of your life. The job that takes 36 seconds to do that

you're going to do for the rest of your life. I don't know a better

definition of alienation than that

From here, Glaberman explains that it is that alienation "which is at

the root of working class resistance and working class struggle. It is

the kind of thing which is virtually impossible to measure [...]

Revolutions are made [...] by ordinary people with all the limitations

of the society, driven by 36 seconds for the rest of your life".

Glaberman also led a Capital reading group in Detroit with black autoworkers forming the executive committee of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, an experience he mentions in The Workers have to deal with their own reality and that transforms them. He also wrote the fantastic book, Wartime Strikes,

about the wave of wildcat strikes by autoworkers following World War

Two in defiance of the 'No Strike' pledge signed by their union.

An argument often heard in Marxist (and anarchist) circles is that

feminism 'distracts' from the 'more important' issues of the class

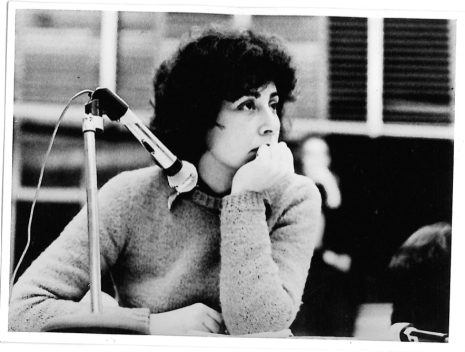

struggle. Dalla Costa

shows why this is nonsense, setting out a highly original fusion of

Marxism with feminism and engaging in years of class-based feminist

activism both in Italy and internationally.

Born in Treviso, Northern Italy, Dalla Costa was active for many years with the Autonomist Marxist group Potere Operaio (Workers' Power) before founding Lotta Feminista

(Feminist Struggle), who not only challenged the sexism rife in Italian

society but also the workers' movement and radical extra-parliamentary

left. In 'The door to the garden: feminism and Operaismo', Dalla Costa describes how leaving Potere Operaia

was "a matter of dignity" as "the relation between man and woman was,

particularly in the environment of intellectual comrades, not

sufficiently dignifying".

Dalla Costa co-authored (along with Selma James) arguably Lotta Feminista's most significant text outlining their Marxist feminist analysis. In The power of women and the subversion of the community,

Dalla Costa demonstrated that, not only did women's domestic labour

reduce the cost of reproducing labour but also produced surplus value.

As such, Dalla Costa was the first of the Italian operaismo movement to

advance the idea that the extraction of surplus value could happen

outside the sphere Marx had designated as the direct process of

production, an idea which would become central to the

extra-parliamentary left in Italy.

Dalla Costa's pamphlet would become highly influential within the

international women's movement and in Italy she would be involved in

numerous feminist groups promoting 'wages for housework' and the

newspaper Le operaie della casa (The House Workers). In 2014, Dalla Costa donated a wealth of documents from her decades of activism to the Padua Civic Library,

which now holds the 'Archivio di Lotta Feminista per il salario al

lavoro domestico' (Archive of Feminist Struggle for the wages for

housework struggle).

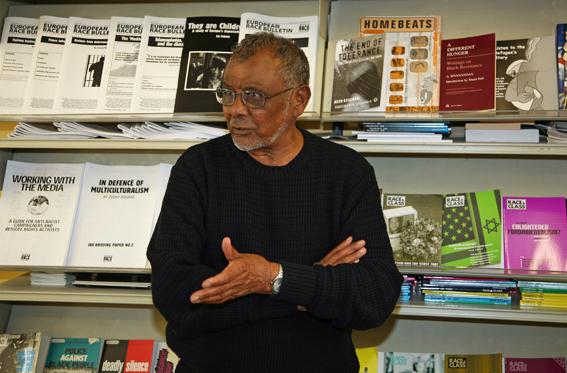

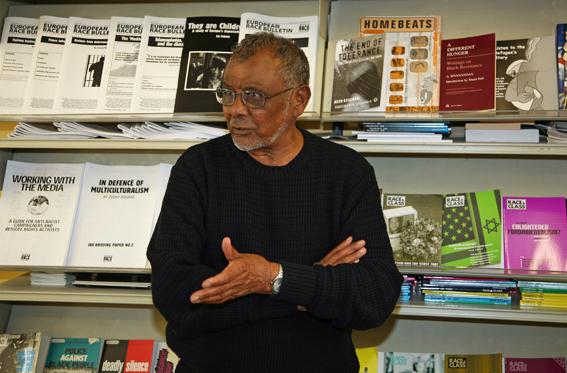

Born in Colombo, Sri Lanka, the son of a Tamil postal worker, Sivanandan

left the country after the anti-Tamil riots and pogroms of 1958.

Settling in the UK, he trained as a librarian, working in several public

libraries before being appointed chief librarian at the Institute of

Race Relations (IRR) in 1964.

In 1972, a major schism took place at the IRR: until then, the

organisation had been moderate and scholarly, attempting to address

‘race relations’ issues and advise government policy. However, a sizable

section of IRR staff (including Sivanandan) took issue with this

orientation and challenged the board to redress it. The majority of the

board resigned and the IRR reoriented itself towards supporting

community organisations and building a black-led anti-racist movement in

Britain. As Sivanandan, now the new IRR director, explained:

Quote:

We did not want to add to the tomes

which spoke in obfuscatory and erudite language to a chosen few, we no

longer believed in the goodwill of governments to listen to our reasoned

arguments. There was a whole lived experience – often not quantifiable

in surveys – of police brutality, racial violence, media distortion,

miseducation and marginalisation that it was now our duty to speak, if

not to, then certainly from.

Sivanandan took over as editor of the IRR's quarterly theoretical journal, Race, renaming it Race & Class

to highlight their interrelationship. The journal was intended to

inform activism, to encourage thinking "in order to do", linking "the

situation of black workers in Britain and the liberation struggles in

the underdeveloped world" with the aim of building an autonomous black

working-class politics in Britain (something often neglected in the

traditional left and trade union movements). He has also written widely

on racism, capitalism, police brutality and black anti-racist struggle in Britain, with many of those essays appearing in his book, Catching History on the Wing.

Libcom.org

Länk: https://libcom.org/blog/6-underrated-marxists-dont-get-enough-love-16102017